The Baby Farms of Tallaght

The Baby Farms of Tallaght

For many years in the first half

of the twentieth century, much of the agricultural hinterland around Tallaght was commonly referred to as “The Baby Farms”- notably the hills above Tallaght-

around Mount Pelier (or Pelia),

Bohernabreena, Piperstown, Ballinascorney, Glassamucky and Killinarden Hill. Baby Farms were

not unique to Tallaght, to Dublin, or indeed to Ireland. Nor were they

new. The practice had been common in the

previous century, and was from the 1860s subject to regular criticism, scandal

and outrage, though perhaps not robust enough legislation, reform or

inspection.

Baby Farming, involved the

‘fostering’ (and sometimes trading) of other people’s children for a fixed

upfront fee, a regular payment, or occasionally both. It routinely involved ‘registered’, and ‘unregistered’

children or infants. Under The Children

Act, one was legally obliged to register a child taken in, within 48 hours,

with the Local Union (South Dublin Union for Tallaght) and later the local authority. Registered Children under the age of seven years

were typically ‘put out to nurse’, while older registered children between seven and sixteen years were ‘boarded out’. These homes were,

in theory at least, subject to occasional inspection. Many children were unregistered. Unregistered children could, and indeed often

were, traded. One could take an

unregistered child with an upfront payment of £10, and then pass the infant or

child to someone else who was willing to take it in, for a payment of £5. Birth mothers, wanting assurances that their

child had gone ‘to a good home’ might take comfort in a higher price, though

few in reality could afford it. And

those in greatest poverty, had the lowest price. Invariably

the unregistered child could end up with the person least capable of providing

for it. It is a profoundly sobering

thought.

The proliferation of unwanted or

uncared for children in Dublin, rather tragically, was nothing new. In the 1700s the Foundling Hospital, on James’s

Street in Dublin, gradually became “one of the largest Baby Farming Institutions’

and found ever more imaginative and inventive ways of responding to the issue. In October 1730 they ordered “That a turning

wheel, or a convenience, be provided by the gate, so that at any time day or

night, a child may be laid in it, to be taken in”. It was supposed to provide for unwanted

children. However the children were not

much wanted in there either. A hospital

nurse in the Foundling Hospital, giving testimony to a committee of inquiry,

informed it that children were given a medicine, appropriately called “The

Bottle”, at regular but indiscriminate intervals. Once they had received their medicine, the

children ‘became easy for an hour or two after it’. Nobody seemed quite sure as to what exactly

the medicine was. Of five thousand children admitted to the

Foundling ‘Hospital’ in the five years between 1791 and 1796, only one solitary

child reportedly ‘recovered’. When the facts

were put before the House of Commons, it unhesitatingly recommended the closure

of the hospital.

Widespread poverty, a shortage of

housing, overcrowding, no birth control, and a conservative moral environment,

made the giving-up, or abandonment of infants and children a far more common

occurrence than you might expect, or indeed historical or contemporary reports

might reflect.

It was a time when expectations

were low, regulations poor and inspections inadequate. It was also a time when ‘turning a blind eye’

was common place and suited most parties, and accountability often sacrificed

for expediency.

The more families in a community

who engaged in the practice of unregistered Baby Farming, the less likely it

was that anyone in the community would report it to the authorities. Even where

children had been registered, in the days when inspectors routinely travelled

by bicycle or horse and trap, if they travelled at all, the hills and

agricultural hinterland, was not so easily or conveniently accessible, and did

not lend itself to, or encourage regular inspection or routine visits. The demand for cheap agricultural labour and

the anonymity that relative seclusion provided for unregistered children, was

seductive. And it generally only came to

light, if the child was involved in a serious accident that demanded external involvement

or attention.

Over 20 years ago, in 1998, I

interviewed some of Tallaght’s oldest residents, for a small local history publication

“Since Adam was a Boy: An Oral Folk History of Tallaght.” Many of them remembered and spoke openly

about the baby farms and the children some local people called “rearers”- the

children reared on the farms. Memories and reports varied widely.

An elderly resident who had lived

at the Four Roads, on Killinarden Hill in the 1940s, Esther McCabe, spoke

candidly:

“Everyone around here fostered kids,

everyone. Some of them were very cruel

to them, those poor kids that were fostered.

It was mostly boys, because they could work harder and people would be

afraid to foster girls in case they would be going off and having babies. The people would only be paid until the child

was sixteen, and after that the child would have to go off and get work. But if

they couldn’t get work, some of the families around here wouldn’t want to know,

wouldn’t feed them or anything”.

“God tonight, I saw some cruelty in my day! A lot

of people around my way would keep hens and fowl, and the leftovers from the dinner-

the vegetables and potatoes would be kept in a bucket out the back to feed the

hens. It might be there a week or

two. I remember some of those poor

children that were fostered, only after turning sixteen, and they asking if

they could have the leftovers for to eat, they would be that hungry. They would eat the vegetables cold and

whatever else was left out the back for the hens. People would call the foster kids rearers, because

they were reared on the baby farms They

would be fostered out of the South Dublin Union. Many of the farmers up in Bohernabreena fostered four, five, maybe six kids.

Another older resident who lived in Bohernabreena from the 1930s recalled:

“All that country above and below that area (Bohernabreena),

was known as the Baby Farms. It was

called that because every family up there, bar one or two, had children taken

in from the institutions to be reared. The

families would get so much a week or a month, from the institution, for keeping

the children. Some families would have

three maybe four, maybe five children taken in.

It seemed like a handy way to make a few bob. Then when the child reached sixteen, that was

it! The allowance would be cut. The families didn’t like them being called

Baby Farms, but that is what they were I suppose. Hundreds of kids were reared up in those hills above Bohernabreena. They were reared

well, went to school with the rest of the children, well dressed and had plenty

to eat, as well as anyone else.

Matt

Dunbar, in an interview in 1998

Children had been officially “boarded

out” or “sent to nurse” to the hills above Tallaght since at least the

1880s. In 1885, 13 year old Julia

Cummins and 12 year old Julia Ward, were placed from the workhouse in South

Dublin, to a farm at Ballymorefin, Tallaght Co. Dublin. One might have assumed their change in

circumstance, would be a welcome improvement on their time in the workhouse.

But less than two weeks later they both absconded from the farm. Police

and others “requested to endeavour to discover the whereabouts of the girls,

and assist the Board of Guardians to recover custody of the girls”. The public were cautioned against harbouring

the girls or taking them into service, without acquainting or obtaining the

consent of the Board of Guardians. Offenders

would be prosecuted.

“More through carelessness than neglect”

In November 1912 Sarah Mc Donald

was only 4 months old, when she was placed ‘at nurse’ with Mrs Mary Lawlor in

Oldcourt, Tallaght. Several weeks later,

on the 23rd November, Mr Joseph Brown, an Inspector with the

N.S.P.C.C., visited the home and found the infant in a back room lying on a

sack of chaff, covered with an old jacket. The baby was very emaciated, with

parts of the body red and scalded. He visited again two days later, and found

the baby still lying on the sack of chaff, but clean. He noted the scalds on the child’s body and

neck and advised Mary Lawlor on how to treat the scalds. The child was delicate

and vomited up its food- Neave’s Food and Swiss Milk. Brown directed Lawlor to take the baby to the

doctor. Lawlor failed to take the child

to the doctor, and when Brown visited some days later he again directed her to

take the baby to a doctor. He made an official report to the Society, who

directed him to remove the child to the South Dublin Union on the 13th

December.

Lawlor had also been visited by Mary Donnelly, an inspector under the Infant Life Protection Act. She told Donnelly she had been feeding the infant bread and milk. Donnelly advised that that was not an appropriate diet for a four month old baby. She instructed Lawlor to get powder to treat the scalds on the baby, and also instructed her to take the child to a doctor. When Donnelly visited again, Lawlor had not carried out her instructions. Sarah McDonald was removed to the South Dublin Union on the 13 December. A couple of days before she was removed, Mary Lawlor had finally brought the baby to the local dispensary. Dr P.J Lydon examined the child and found it “delicate, in an advanced stage of marasmus while its hands twitched frequently as if it were suffering badly from colic pains. There was also a little scalding”. He held out little hope for the child’s recovery.

Little Sarah McDonald died of malnutrition

days later in the South Dublin Union.

Miss Mary Donnelly, gave evidence that Mrs Lawlor had failed to carry

out her instructions but this was ‘more through carelessness then neglect’. The verdict held that the child died of

malnutrition due to its failure to assimilate its food. Many children were extremely delicate and

vulnerable, when being put out to nurse.

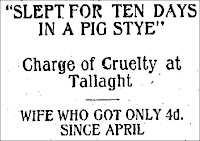

Being incapable of looking after

your own children, was no bar to adopting others. The Lawlor’s next door

neighbours in Oldcourt, Patrick and Eileen Dunne were brought up on charges of

wilful neglect the following year. The

Dunne family had three children of their own- Daniel (7), Thomas (9) and Peter

(12) and had adopted a young girl, Mary Boland. Mary Boland, while adopted by the Dunnes,

slept in Lawlor’s pigsty next door.

Inspector Brown found Mary in a shocking state- starving and with barely

any clothes. When the Dunnes were

evicted from their cottage in April 1913, they went to stay with Patrick Dunne’s

sister in Firhouse, but were put out after Eileen Dunne quarrelled with her

sister-in-law. Patrick Dunne worked

fairly consistently, but had reportedly given his wife only 4d in five months

for food for the children. When brought

before the court Eileen Dunne, presented with a black eye, which she claimed

was caused by her husband. He claimed

she had been drunk and had fallen over.

Dunne’s children were left to wonder the roads of Tallaght, begging for

food, saying they were starving. Dunne

was sent to jail for three months with hard labour. His adopted daughter, little Mary Boland, who

had been sleeping in the neighbours pigsty, was sent back to the South Dublin

Union, pending her removal to an Industrial School.

Child Neglect was by no means

confined only to Nurse Children, Boarders or “Rearers”. In 1911, Edward and Catherine Hughes of

Oldcourt were prosecuted, at the instance of the Society for the Protection of

Cruelty to Children (NSPCC), before Tallaght Petty Sessions on charges of

Neglect and Cruelty to their seven children. Together the couple lived in a

house, which was described in court as ‘practically a ruin’. Five of the seven children were under ten

years of age. When visited by Inspector Brown,

“The condition of affairs in the house was absolutely disgraceful. The house

was in a most filthy condition, part of the roof tiles were missing entirely,

and the rest of the roof had several holes in it. There was no door or window in the ruin, and

old sacks hung in their place. There was only one bed, which was covered with

straw and old sacks, and the floor was strewn with straw and rags on which a

dog was lying. Some of the children said they slept on the floor, and indicated

some stones on which they used as pillows. The children were nearly naked and

there was no food in the house”.

Inspector Brown, visited at least

four times, sometimes bringing clothes from the NSPCC for the children. On his final visit he found the clothes scattered

and trampled in the straw on the floor.

Dr Caleb Powell also visited the house on several occasion, and bore

witness to Inspector Browns findings. He

said in all his experiences he had never seen anything to equal the awful

conditions in the house. The children

were in a filthy condition and one little girl aged three was entirely

naked. Mr Moran for the Society

requested the magistrate to issue a warrant for the arrest of Mr Hughes and

also for Mrs Hughes, and that an order be made to have the children sent to the

South Dublin Union. The Bench agreed to

Mr Moran’s request, but released Mrs Hughes out on bail until the next court

sitting.

A Family Matter

It was a time when people kept

themselves to themselves. Family matters

were private matters, and an unregistered child could easily be passed off as a

niece, a nephew or distant relative who had come to stay, as was often a reality,

where many large families inhabited confined and inadequate housing. Raising concerns about the welfare of other

people’s children, and in particular children either sent ‘out to nurse’, or simply

taken in, was not always appreciated.

In 1916, Miss Mary Shields from

Clondalkin, was brought up before Tallaght Petty Sessions, on charges of having

assaulted a nurse child, Patrick Doyle.

Extraordinarily, Patrick was in the care of another woman- Mrs. Doran,

who had a number of children, “boarding-out” with her. Ms Shields, with good intentions, brought a

very reluctant Patrick Doyle to the local barracks, and reported that he was

being mistreated in the care of Ms. Doran. In evidencing her claim, she stripped the child in the barracks. The child bore ‘only a slight mark’ of being

mistreated, and it was Ms Shields who subsequently found herself charged with

assault, for having undressed the child.

She was bound to the peace for the assault, and reprimanded for

interfering with Mrs. Doran.

On the same day that Mary Shields

was charged in Tallaght, a verdict was delivered on the death of an

unregistered Nurse Child in Dublin. Four

month old Mary Donnelly died from malnutrition after being brought to Patrick

Dunns hospital in Dublin City. Mrs H

Connor of Townsend Street, only had the child four weeks and received 12s a

week for its care, when it took ill and expired. She had been aware that a nurse child should

be registered, but claimed she didn’t realise it should be registered within 48

hours.

Enough is Enough

Thomas Cahill was only a small

boy when he was sent from the South Dublin Union ‘out to nurse’ with Margaret

Miley and her husband on their farm in Ballinascorney, where he stayed until he

was 16 years old. As such he was a

‘registered’ boarder. He worked hard on

the farm during the day, and liked to read ‘Penny Dreadful’ comic books and

cheap and exciting literature, by candle light in the evening. On Friday evening the 24th

November 1910, Thomas Cahill and Mrs Miley (42) were alone on the farm. Her 59

year old husband and gone to town. Cahill

(16), had had enough of Ballinascorney and enough of the Mileys. He approached

Mrs Miley and demanded money, saying either she give him a pound or he would go

upstairs and take it himself. Mrs Miley

refused to give him any money and went out to the dairy. A few moments later Cahill followed Mrs

Miley, meeting her as she returned out of the dairy shed. He drew a revolver from his pocket, pointed

it at Mrs. Mileys head and fired it, from a distance of only two feet. The bullet struck her on the forehead,

glancing off it. Margaret Miley slumped

to the ground, unconscious. When she

regained consciousness, she managed to walk the half mile to her sister’s

house. Cahill fled across the fields, before later being picked up by Constable Humphreys from Brittas. Cahill was arrested, and

returned to the farm. He showed Sergeant Farrell where he had hidden the

six-chamber revolver in a rabbit burrow, with 33 cartridges. Only one of the six chambers was empty.

Sixteen year old Cahill was charged with attempted murder. Cahill claimed Mrs Miley was in the habit of abusing him and that he had told her and her husband, that someday he “would make them pay for it”. On the day in question, Cahill claimed he had been threatened by Mrs Miley with a spade. He noted that Margaret Miley “Must have a head like iron to still be on her feet”. Cahill was remanded in custody, while Mrs Miley “progressed favourably”.

Sixteen year old Cahill was charged with attempted murder. Cahill claimed Mrs Miley was in the habit of abusing him and that he had told her and her husband, that someday he “would make them pay for it”. On the day in question, Cahill claimed he had been threatened by Mrs Miley with a spade. He noted that Margaret Miley “Must have a head like iron to still be on her feet”. Cahill was remanded in custody, while Mrs Miley “progressed favourably”.

Census Returns 1911

A cursory glance at the 1911 census

returns for Tallaght give some indication as to the scale of officially “boarded

out” children, or infants “At Nurse” in Tallaght. The 1901 Census returns are not dissimilar. These are of course only the ‘official figures’,

and give little indication as to the scale of ‘unregistered’ children, taken in

in the district. Children could be

variously identified as nurse child, boarder, lodger or visitor. Their ages, names and place of birth can give

some clue as to their status.

Almost all

the children registered as ‘boarded out’ were from Dublin City. Many families of modest means had ‘servants’,

often boarded out children, who had come of age and stayed on with the family.

Margaret Smyth, a 65 year old widowed farmer, in Corrageen, Tallaght,

lived with her two sons and a daughter.

She had 2 boys, boarding, and a 9 year old male ‘visitor’ from Dublin

City.

Patrick Saul, a 38 year old Farmer in Glassamucky, his 60 year old

brother and 50 year old widowed sister, had four young girls taken in from

Dublin City, all aged between ten and fourteen years.

Ellen Walsh, a 72 year old spinster in Piperstown had three boarders

all under thirteen years of age, all from Dublin City.

Elisabeth Conlon, a 69 year old farmer in Corbally, had three young

boarders, all male between ten and twelve years.

Jane Flood, of Cunard, a 73 year old, had four boarders between the

ages of nine and fourteen years.

James Corcoran, a 70 year old Widower and farmer had three young

boarders, between nine and twelve years, all from Dublin City.

Esther Carthy in Tallaght Town, a 29 year old, had four ‘nurse’

children under seven years.

Mary Loughlin, a blind and illiterate spinster and farmer in

Killinarden, had two girls taken in from the city, aged 11 and 12. Mary was assisted by her cousin who lived

with her.

John Lawless in Killininny, an illiterate sand contractor and his wife,

had two infant girls, both nine months old, at nurse.

Susan Ford in Kilnamanagh, a 62 year old Widow, had three children

taken in, two boys, six and eight and a six month old infant girl. (Ten years

earlier in 1901, she had four boarders and a 10 year old ‘visitor’ from Dublin

city)

The Doyles in Mountpelier had three Boarders under thirteen years of age.

Anne Carty in Mountpelier, had two male boarders, both under twelve years.

Peter Grant and his wife, both 70, had two boys taken in, both under thirteen years.

The Ledwidge Family in Old Bawn, in addition to their own seven

children had two young boarders.

Teresa Walsh, an 87 year old widow in Piperstown had two boys, thirteen and eleven years.

*

Get Rid of the Boy

In 1924 Mary Kilbride, of

Allagower, Tallaght, was charged at Rathfarnham District court of having failed

to send a young boy, who had been sent

to nurse with her, to school. The Justice

noted that children should only be sent to nurse, to people who would care for

them properly. Kilbride responded that

she would be glad to get rid of the boy.

The Justice said he would bring her remark to the attention of the

commissioners, and promptly sent the boy to an industrial school. He “hoped” that the department of finance

would make proper provision for the maintenance of children sent to industrial

schools, under the School Attendance Act. Mary Kilbride, the youngest of three

spinster sisters, had been rearing nurse children from Dublin City for over 20

years.

Nobody's Child

In 1932, Bridget Clarke and James

Curley, both from Longford, abandoned their infant child in Tallaght, Co.

Dublin. They abandoned the infant in

the hope that it would be found and taken to a house, by a kindly Samaritan. Their defence solicitor, Mr. J Barrett,

claimed that the young pair were in a state of panic and had no friends to

consult. Curley was sentenced to six

months with hard labour while Clarke was let out on the condition that her parents

took her back in. What became of the infant was not reported. It was a common story for the time.

In late October 1934 on a

Saturday evening, a Tallaght man was walking down the Cookstown Road, when he

heard what sounded like a baby crying in a hedge. On investigating the cry, he

found a two month old male infant abandoned, lying concealed in a straw fish

basket under a bush by the side of the road. The infant was taken to the Garda

Barracks in Tallaght, before being transferred to the South Dublin Union. It was an unremarkable incident, that merited

less than eight lines in the paper.

It was by no means a new

phenomenon. Seventy years earlier concern

was expressed about the increasing number of children being abandoned. When Margaret McDonnell pleaded guilty to

abandoning her child on a Tallaght road in 1860, Mr. Justice Hayes, sentencing

her to four months imprisonment, observed that the crime of child desertion was

becoming increasingly common in the county.

The Department did not seem to mind

The problem of abandoned and

neglected children, continued on well into the 1940s, as did arrangements, both

formal and local.

Families could unofficially

‘adopt’ a child and pocket between £5 and £10, but then later apply for relief

from the union or Board of Assistance for their maintenance. Often families

could take four or more children, on such terms. The death of a “board-child” in 1941 gave

rise to the first suggestion that perhaps babies put out to board should also

be provided with a “paid for cot”.

Patricia Ardiff, a two and a half year old child died from hemorrhage,

likely caused by a fall. The child had

been placed sitting up in a large drawer placed on two chairs, and fell back striking

her head. Several days earlier the same

child had struck her head on a fender.

*

In recent decades much attention

and inquiry has focused on defined institutional settings- Industrial Schools,

Mother and Baby Homes and the Magdalene laundries. It is perhaps easier and more comfortable

for a society, to explore and investigate the actions and behaviors of large

institutions, of the more easily defined “Them”, rather than of “Us”. The Baby Farms kept no files, no records and

no notes.

But the Baby Farms were very

close to home indeed. They were not

hidden behind the tall and ancient enclosures of institutional walls, or run by

veiled and faceless characters with assumed names, who had taken vows of silence

and obedience.

The Baby Farms were run by your

neighbours and mine, perhaps your great-grandparents or mine. And they were hidden behind nothing more than

a cloak of silence, an Irish Omerta. Like

the institutions, they reflected at various times, the very best and the very

worst of the communities they constituted and the communities they served. For the most part, they were run by people living in difficult conditions

through difficult times, trying to help others and themselves, as well as they

knew how, in accordance, though not always, with the changing standards and

expectations of the day.

In every community the brightest

light as the candle fades, can sometimes cast the longest shadow. Some only remember the warmth of the flame,

and some the darkness around it.

I will leave the final word, to

one who remembered so vividly, The Baby Farms of Tallaght:

“I remember one fellow that had been fostered

and very hard reared, and went off and got three jobs- killed himself with the

work, to give to his children what he never had himself. Though his mother-in-law got the drop of her

life when her young-one went off and married him, he made Kings and Queens of

his children. All those lads, when they

got married, by God they treasured their children. They all went off and had big families of

their own and treated their children like Lords and Ladies”.

(Mrs

Esther McCabe, in an interview in 1998)

Superb, fascinating piece Albert - shines a light on a darker aspect of Tallaght's and Ireland's shameful history in the treatment of its children.

ReplyDeleteCheers Dermot. Thanks for the feedback.

DeleteExcellent piece, very interesting & insightful.

ReplyDeleteThanks for the feedback. Much appreciated.

DeleteMy father was 'adopted' by the Connor family in Main Street. He and his three brothers appear in the 1911 Census asliving with the Connor family.

ReplyDeleteA great read

ReplyDeleteThank you.

DeleteVery sad but interesting too, Patrick and Eileen Dunne were my great great grandparents, and it would seem they were not very nice people. I love doing my family history but learning something like this about my ancestors feels like a kick in the guts.

ReplyDeleteWhat your ancestor did is no reflection on you

DeletePatrick & Eileen Dunne would have been my Great Grandparents. Definitely not the kind of people I’m happy to add to my family tree. It’s quite upsetting to know they were related. It Seems they not only abused their foster child but their own kids. Good old Catholic Ireland. No food for the children but plenty of money for drink and then off to mass on the Sunday.

DeleteSo glad, that these accounts are being published, high time that the truth is out there, no matter, how painful.

ReplyDeleteExcellent factual account of a dark ,unspoken and cruel history , Ireland and it's treatment of its helpless, vulnerable and displaced children. Thankyou for sharing this rather remarkable piece of history with us .A thoroughly informative and extremely enjoyable read.

ReplyDeleteThank you for the feedback. Glad you enjoyed it.

DeleteVery interesting read. I can only imagine the suffering that a lot of these poor children must have went through. At least they are being remembered in writing such as these.

ReplyDeleteThanks for the feedback.

DeleteSo sad shameful ,did nobody care,did they think children had no feelings or memory, people talk about the good old days, good old days ,,not for so many innocent children,,,shameful

ReplyDeleteAlbert. I had no idea. I’m astonished. You’ve done us a great favour by telling these stories. I’m beginning to realise that I knew some of these people. Thank you and congratulations on fine work. Kieran Fagan.

ReplyDeleteThank you very much Kieran. It is a tale I became aware of back in 1998, but I sat on it for over 20 years out of respect to the many families and Individuals in a small community, for whom it was still a reality. But after so many revelations and scandals'in the intervening decades it feels timely to inform and to deepen the narrative and provide a broader context, to what is a very complex story, often presented as a simple Good V Evil Story. I hope it widens and deepens peoples understanding, the discussion and debate.

DeleteGreat read. My mam found a naked 3 yr old boy in tallaght town centre carpark across from the priory around 1985 we had to drop him to the garda station that night and never heard another word. It haunts me to think about him.

ReplyDeleteMy Grandfather's baptism record notes that he was "at nurse" in Tallaght. He was raised by a family that were good to him and although I have a good idea who his father was I don't know who his mother was. When I was a child I was told not to ask him about it as "it would upset him". So very sad. I think he was told that his parents had gone to America and that they would send for him when they were settled. Nobody sent for him. I know he was luckier than a lot of children but I feel a deep sorrow for him and his birth mother.

ReplyDeleteA very informative piece thanks for sharing truly hard times

ReplyDelete